Contributed by Robin Hill / The works in “Assembled,” an absorbing three-person exhibition featuring Julia Couzens, Helen O’Leary, and Cornelia Schulz at Patricia Sweetow Gallery in San Francisco, are defiantly not about anything but are, rather, of many things (of fiber, wood, paint, wire, canvas), and have been realized through many actions (binding, wrapping, stuffing, leaning, interlocking, slathering, skimming, stitching, gluing). The works ask to be read, thread by thread, fragment by fragment, layer by layer. Each artist is deeply engaged with the physical properties of matter, and the ways in which space, time, and gravity are activated. Conditions resulting from material in relation to an action connect the works in the exhibition and, intentionally or not, offer poetic correlations to our everyday, lived experiences.

Julia Couzens’ work considers constraint, friction, and tension as sculptural conditions. There is fierce and sinister energy behind her twisted, wrapped, and woven fabric forms, which resolve into small pillow-like gyres that she refers to as “bundles.” Her selection, dissection, and deployment of garments and home décor run the gamut from natural, synthetic, tacky, and elegant. Hierarchies among the elements are wholly absent. Tulle, polyester, cotton, and wool, encrusted with an array of notions, are enlisted for their mark-making and density-building potential. Striving to be a grid but failing, having the allure of softness but being itchy, seeming to signal comfort but being full of conflict, are at the heart of the work. It inspires us to embrace discomfort and uncertainty, and instills an awareness of our own unrest. Gertrude Stein’s treatment of an object in her poem, “A Carafe, that is a Blind Glass,” offers a literary parallel to a reading of Couzens’ work. She writes: “All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.”

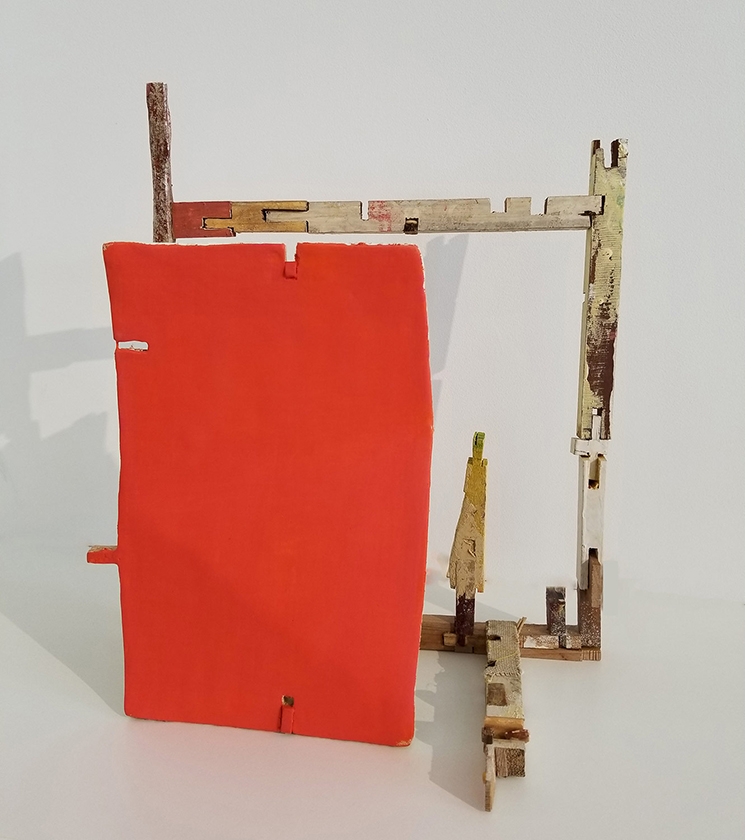

Helen O’Leary’s work blurs the boundaries of painting and sculpture. Made of repurposed wood, her structures support delicate expanses of painted canvas. The work conjures a condition of vulnerability and strength, while also entertaining a quirky conversation with upended jigsaw puzzles, the reverse sides of billboard scaffolding, and drive-in movie screens. Like a broken bone in relation to a cast, O’Leary’s work inverts the role of structure in relation to that which it supports. The structure becomes the subject. An incremental, sequential reading of the elements of the work calls to mind James Weldon Johnson’s spiritual song “Dem Bones,” which notes, familiarly: “Toe bone connected to the foot bone. Foot bone connected to the heel bone. Heel bone connected to the ankle bone….” Beyond the obvious description of a body as a whole of connected parts, the song’s original theme of death and resurrection resonates in O’Leary’s work, in which precarious balance signals collapse.

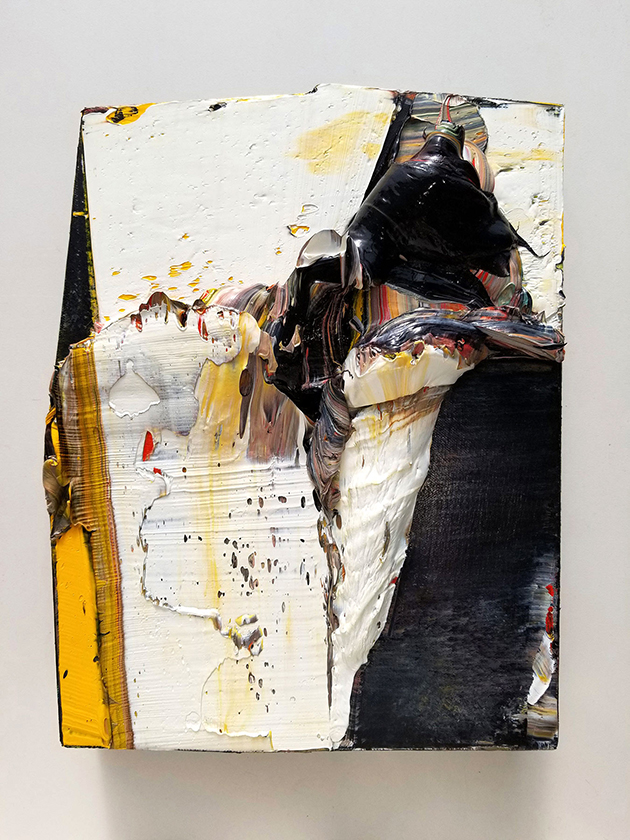

Cornelia Schulz employs paint as a physical building material. Canvases stretched over subtly shaped panels support pounds of viscous paint which alternately reveal and conceal seams of color. Paint flows downwards toward the floor, like slow-moving lava. The shapes, lines, and color operate as cross-sections of a geological event frozen in time, and therefore emit a quality of inevitability. “It is going to happen,” the paintings seem to say. The particular “it” one ascribes to the work is open-ended, but the implied movement of her material coalescing in alternating states of order and entropy is the primary appeal of these works. Schulz has a kindred spirit in her late contemporary Robert Smithson through his somber and environmentally-aware earthworks, Asphalt Rundown and Glue Pour. Their work shares a sense of our human scale, as it pulses between the miniature and gigantic.

In his 1971 Norton Lecture, The New Covetables, Charles Eames affectionately meditates on goods and what they offer in terms of potential (kegs of nails, balls of twine, barrels of apples, reams of paper, boxes of chalk, cords of wood). His feeling is that, in their unopened and unused states, these goods will last forever. In the aftermath of a break-in of his wife and fellow designer Ray Kaiser Eames’s car, Charles laments that “everything had been strewn across the lot…. I came upon a bolt of cloth, this was really stressing. This was a bolt of wool that when you take hold of it you can feel the animal wax and oil. What was shocking was that the guy had not thought enough about it to take it. A bolt of cloth comes under that heading of goods, the kind of goods people lay great store in, the kind of goods that people have tremendous security about.”

The artists in “Assembled” share a common language in their formally rigorous yet refreshingly eccentric engagements with goods. Each has laid “great store” in a material, and its ability to speak about itself. Our familiarity and attraction to their materials draws us in and then suddenly leaves us on our own, to assimilate forms of becoming and unbecoming, assemblage and dis-assemblage, being and non-being. Theirs is an art of assembling but not resembling.

“Assembled: Julia Couzens, Helen O’Leary, Cornelia Schulz,“ Patricia Sweetow, San Francisco, CA. Through November 24.

About the author: Artist Robin Hill focuses on the intersection between drawing, photography, and sculpture. She is a faculty member in the Studio Art Program, Department of Art and Art History, at the University of California at Davis and is represented by Lennon, Weinberg, Inc. in New York.