by Julia Couzens

Combining Sarah Amos’s mixed media fiber paintings with Tony Marsh’s ceramic sculpture is an inspired pairing of elemental force and drama. Together, their work’s thread-laden thickets, painterly scarifications, gnarls, notches, and spewing globules is a resolute volley against the virtual world that is rapidly whisking away our tactile, ground-level experience of life.

In this time of Zoom and Instagram, it’s as if we are flying above our own lives, bodiless viewers scanning bodiless things. Photogenic as their work is, seen in real life, Amos’s dazzling textile fabrications and Marsh’s mesmerizing vessels are primal entities — embodiments of energy, cracking live and urgent – formed by the internal relationships of their innovative processes and the imperiled region of material awe.

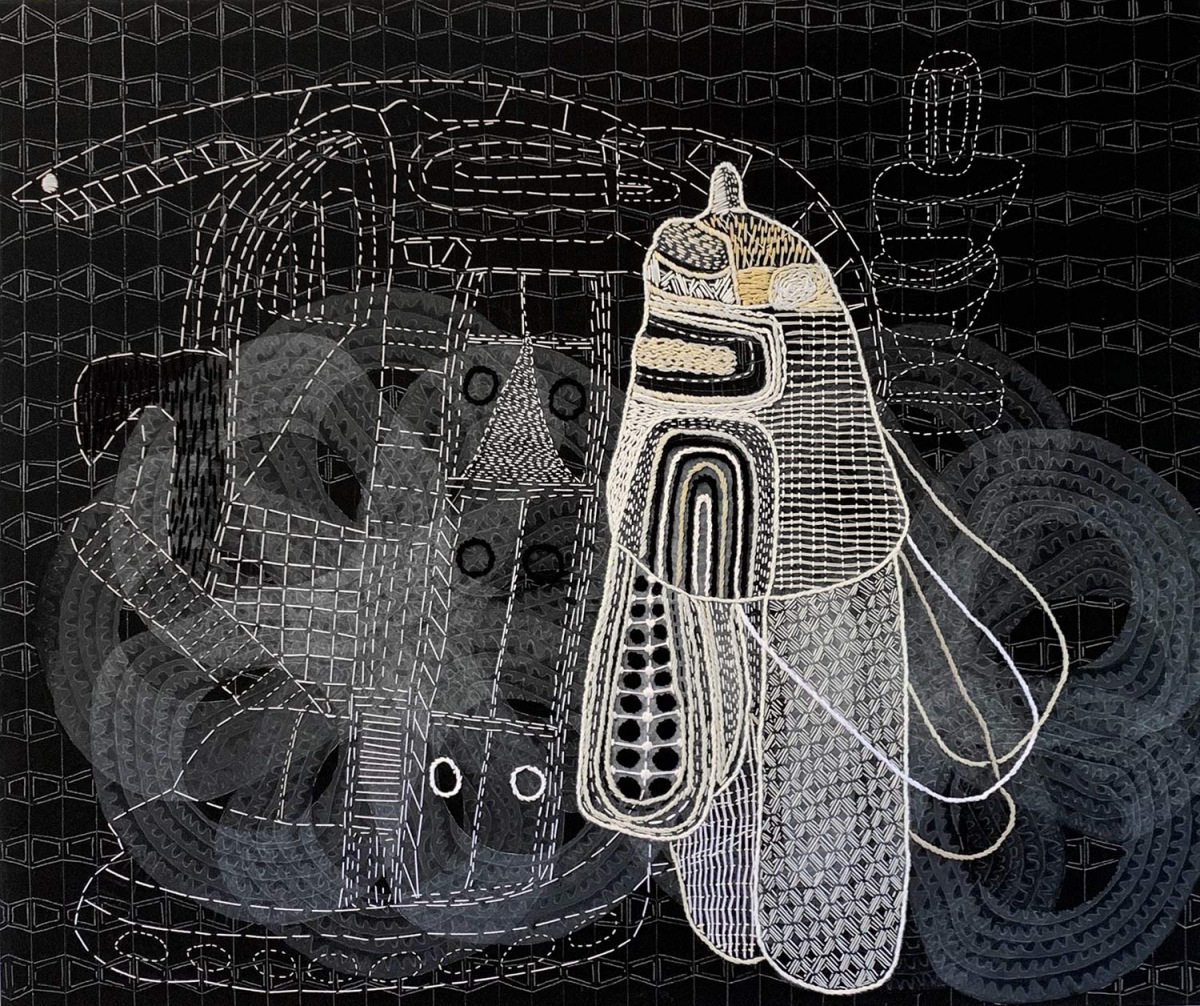

Sarah Amos assembles printmaking, drawing, and stitching into unique, one-of-a-kind fiber paintings bristling with graphic vigor. Shapes both foreign and familiar advance and recede. Abstract mazes coalesce into myriad configurations suggesting dress and costume patterns, charts, diagrams, and in a work such as Lift Off (2019), templates of visionary engineering plans left by ancient civilizations or extra-terrestrial visitations.

A master printmaker, Amos deploys collagraphy to fabricate the initial surface of her ground. Scratching, cutting, and pasting marks, textures, and shapes into cardboard or plexi plates she inks then imprints the collaged plates onto large swaths of thick industrial felt. The imprinted felt is overlayed with armatures of handstitched patterns defined by repetitive vertical, horizontal, and curvilinear lines or invigorated with zigzags and diagonals. Stitching pulls and tufts, sculpting undulations that suffuse her forms with subtle indentations of depth and space. The incremental accumulation of her painstaking needle and thread mark-making prompts speculation on the passage of time, the quality of will, and the physical performance involved in assiduous making.

Amos lives and works between rural Vermont and her native Australia. To be sure, her design elements recall the symbols and graphic sequences of Aboriginal art as well as the bold delineations of contrasting pigment used in bark painting. But her concerns and influences are diverse. Motifs are pushed and pulled in dialogues of abstraction. The meaning of her work may be found as much in its matrix of global textile practices such as tapa cloth from indigenous Pacific Ocean island cultures, Japanese sashiko embroidery, and myriad African traditions. Or in the rigorously ordered worlds of self-taught and “outsider” artists such as Martin Ramirez and Adolf Wolfli.

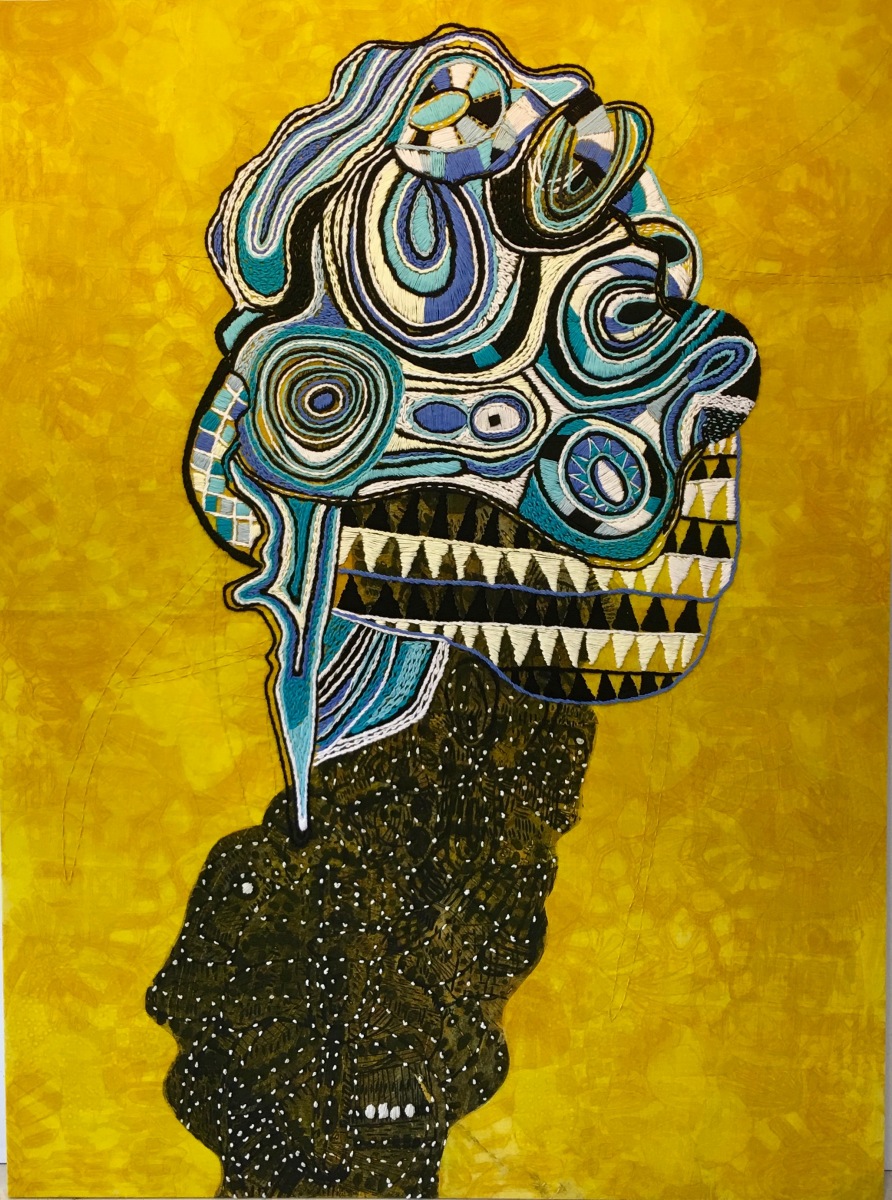

Double Dutch (2019) is a monumental painting of two stacked forms stitched on a faintly patterned yellow ochre background. An amorphously bulging head constructed of black and umber yarns appears to sprout from the bottom of the work. Specks of white thread animate its surface. White embroidered thumb-sized blots define an eye and maybe little white teeth. Perched atop the form like some grand, teetering turban is a coiling mound of aqua, black, and white concentric circles buttressed by rows of black, white, and ochre triangles. Alternatively, it may be another head looking backward. Or forward. The work a portrait of a stitched Janus presiding over gateways and the vacillating theater of life.

Tony Marsh’s pitted, gnarly, encrusted ceramic sculpture is a bare-knuckled exploration of color, light, texture, and form using the vessel as his touchstone and tabula rasa. The individual works are untitled, but he presents and refers to them under the title of Cauldrons & Crucibles. Appearing to be mauled by both numinous and terrestrial forces, the forms conjure reveries on devotional acts, ritual fire, and ruminations on nature’s transformative stew. To the extent cauldrons & crucibles are used as instruments in service to regeneration and change, the designation is fitting.

Encountering Marsh’s cauldrons, one may see something stupefyingly beautiful, or cadaverously sooty, though always something demonstrably itself. But Marsh sees evidence of his method: the time, craft, and attention paid to every aspect of the alchemical phenomena permeating the work. He subjects himself to methods that are performed with incremental gestures and that lead to inner realities. Rather than asking himself what something might look like, he asks what might happen? What might happen if glaze is fired over glaze? Then fired again. Or if broken chunks are fired over broken chunks? And fired again? Toggling back and forth between discovery and transformation, Marsh seeks meaning by working through things rather than refining them.

Fired as many as 7 and 8 times the cauldrons are pummeled by fire into virtually monochrome battleship gray husks — pockmarked, dry, and scabrous relics of primal origin. Or emerge swathed in stumpy, ham-fisted patches of cadmium red, yellow, and rust. The initial cylindrical form is always constant, but the layers of glaze and spewed cracking fragments create mutant topographies that sag and grow. Nobs sprout nobs, rivulets seep in ruinous gutters, or alternately inverted in multiple firings, form encrustations of translucent aqua rubble, like fragments of petrified light. Wizard science.