MAY 12, 2023

by Maria Porges

Ramekon O’Arwisters’ career as a sculptor has been characterized from the start by fearless and authentic experimentation with materials. These have included the textiles familiar from his childhood, followed by broken shards of glass and ceramic discovered during an artist’s residency at San Francisco’s Recology/Waste Management. He has since become known for a combination of the two in extraordinary freestanding sculptures he describes as “cultural totems.”

The spare, elegant installation of five sculptures and three black and white photographs in MoAD’s Salon Gallery serves as a small survey, spanning several years (2018-23), allowing viewers to see O’Arwisters’ transition into his current body of work. Shows that take place in this space are limited by the fact that it is also used for talks, conversations and other presentations. For this reason, four of O’Arwisters’ pieces, rather than being visible from all sides, are on pedestals tucked firmly into the wall— a minor shortcoming of this otherwise stellar show, curated by Selam Bekele. The oldest of these pieces, Mending #13 (2017), consists primarily of crocheted strips of fabric that have been manipulated to create a vessel-like form. Fragments of broken ceramic protrude from the piece’s sides, almost subsumed by the crocheted cloth in the way a tree sometimes absorbs stones or fenceposts. The sculpture’s open top invokes its metaphorical function– as a container for healing through repair.

The other works on view exhibit the range of O’Arwisters’ current projects. Additional sculptures as well as dramatic black-and-white photographs communicate a new edge and urgency. While shards and textiles are still present, they are deployed in increasingly bold ways, as suggested by the show’s title: Freeform and Razor-Sharp. The strips of cloth that were originally sourced from recycled materials have largely been replaced by colorful remnants of designer fabrics: still a kind of “leftover,” but far more dazzling than their humble predecessors.

In Cheesecake #8 (2019), these exotic fabrics are present, mostly in the form of braids, but the ceramic fragments now dominate. Three of these thick, dagger-like shards, recycled from broken pots and sculptures made by students at CSU Long Beach, create a powerful-looking tripod of support for a structure built out of more broken ceramics, covered in volcanic-looking glazes and intertwined with cloth and thread. In an interview, the artist explained how a hidden structure, created with rope and various binding knots, makes the visual precarity of the pieces possible.

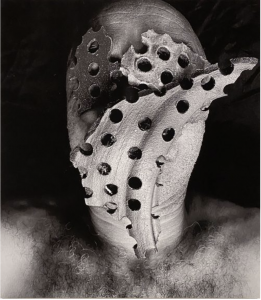

The three photographs in the show are self-portraits, featuring head and bare shoulders, though the face in each is masked by ceramic fragments or textile materials. This strategy allows viewers to project their own emotional experience on these powerfully evocative images—what the show’s curatorial statement refers to as a process of grappling with one’s internal fears and wounds while confronting the dualities of protection and danger. The pictures’ monochromatic simplicity provides a stark contrast to the vivid colors of the sculptures.

One photograph, in particular, seems to suggest a call and response with the sculpture located across the gallery from it, titled Flowered Thorns #11 (2020-21). In both, cascades of fiber suggest the ritual costume of a West African shaman, or perhaps the freighted cultural significance of hair itself. That second reading is enhanced by the sculpture’s vivid braids of brocade and other richly colored fabrics, their bold patterns of green, orange, red and black gleaming with threads of gold that contrast with unraveled burlap still holding the crimped texture of its manufacture.

The two most recent pieces in the show introduce an important new material. Flowered Thorns #13 (2022) is similar in scale and materials to the other freestanding sculptures, with one notable exception. Out of the carefully cantilevered structure of fragments of ceramic “failures” and braided, knotted cloth, what first looks like the thorns referred to in the piece’s title protrude to an improbable length. The long slender lines of black (with a few that are white) have pointed ends. Closer examination reveals that these are zip ties—the kind used as handcuffs in modern policing. Like the shards, they are both menacing and beautiful, interpolated as they are in the artist’s magpie-like accumulation of pretty things that include a dangling bit of rhinestone-covered lace, gold-threaded cloth, and even the gleaming reflections from the glazed surface of the ceramic fragments. Longer contemplation suggests that the purpose of those spikes might be to protect the piece to which they have been attached, creating a zone of power and healing.

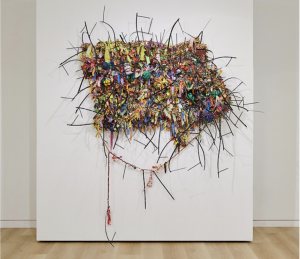

O’Arwisters has used the ties again in the largest and most recent piece. Hung directly across from the door on a small floating wall, the scale and placement of this untitled tapestry made earlier this year give it the kind of meditational power of an altarpiece, ironically appropriate in the shrine of culture that a museum supposedly represents. The piece’s undulating, roughly rectangular crocheted form is almost hidden by dangling ends of the strips of cloth used to make it. A cloud of zip ties bristles out of the

entire surface, interpolated with small bundles of brightly colored leather. Between the mystery of what these wrapped bundles might contain and the protruding black lines of the ties, O’Arwisters evokes the protection and power of a nkisi figure1. He has also suggested that the ties represent restraint—whether emotional, psychological or physical. Reflecting on lifelong experiences of vulnerability as a Black and queer man who grew up in the South, he continues to manipulate his materials to evoke both danger and the sanctuary of beauty itself that lies within the heart of everything he makes.

# # #

Ramekon O’Arwisters: “Freeform and Razor-Sharp” @ Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) to June 11, 2023.

1. Nkisi. A figure or object used for power and protection by the peoples of the Congo Basin of west equatorial Africa.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Sweetow Gallery except where noted.

About the author: Maria Porges is an artist and writer who lives and works in Oakland. Since the late ‘80s, her critical writing has appeared in many publications, including Artforum, Art in America, Sculpture, American Craft, Glass, the New York Times Book Review and many now-defunct sites or magazines. The author of more than 100 exhibition catalog essays, she is a professor at California College of the Arts.