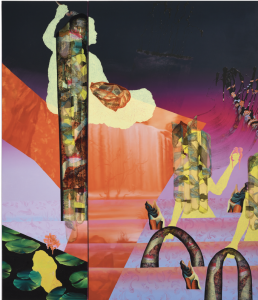

Anne Anlin Cheng’s 2019 book Ornamentalism critically considers the plight of the “yellow woman”— a woman of Asian descent — who, throughout history, has been racialized in a manner inextricably connected to objecthood and aesthetics. For the yellow woman, her adorned, exoticized, and hypersexualized body has been the subject of art and fantasy since the idea of the Orient became part of the European and American imperialist project in the 19th century. In Lien Trương’s painting From the Earth Rise Radiant Beings (2021), from which this exhibition draws its title, the yellow woman and her sisters are given new lives and representations, their silhouettes only providing a suggestion of their forms. Historically, Asian women were seen in “the West” primarily as aesthetic beings, but these silhouetted figures resist our gaze. Across the center of the work, a slash of electric yellow reveals the face of Teresa Magbanua (1868–1947), a Filipina military leader who helped lead resistance movements against Spain, the United States, and Japan. Throughout the painting, disembodied hands reach, stretch, and gesture in all directions, calling us from the forgotten annals of Asian and Asian diasporic record, demanding recognition. How do we attend to the calls of our neglected ancestors, the yellow women of history, like Magbanua?

Liên Trương’s diverse artistic practice hears and responds to these ancestral calls by imagining a future in which such ancestors are liberated across time and space through splintered, concealed, and poetic representations. This exhibition, which brings together different bodies of recent work, showcases Trương’s range as an artist, archivist, and art historian. Her paintings and the collaborative work with Hồng-An Trương, The Sky is Not Sacred (2019), reveal her investigative eye towards history and deep understanding of the various mythologies that serve as the foundation for the American artistic canon. Moreover, she weaves elements of her lived experience as a Vietnamese refugee into her pictures, allowing for dialogic visual encounters between the personal, political, and global.

Trương’s family fled Vietnam during the Fall of Saigon, when she was eighteen months old. Like many artists who were born elsewhere but call the United States home (or some approximation of it), Trương has a critical fascination with American landscapes and their histories of representation. Perhaps it can be said, as many of her works suggest, that displacement can serve as a premise for lifelong meditations on the importance of land and the freedom (or lack thereof) with which people can occupy it. In According to the Spectre of Blood and Water (2019) and Blessed is the Black Silk on Your Dark Little Head (2021), Trương grounds the works with ghostly landscapes of her mother’s hometown, Đà Lạt. In both paintings, the landscape is rendered in a palette that recalls infrared photography — suggesting surveillance, military presence, the mechanical gaze, and all the havoc these forces can wreak. As Ariella Aïsha Azoulay suggests, photographs such as these become “petty sovereigns,” serving the watchful eye of imperialism. How can a land and its inhabitants flourish if outsiders are watching and dictating the terms of existence? What does freedom look like in such a landscape?

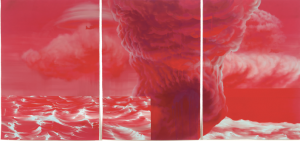

Speaking of landscape: in the darkened lecture halls of art history classrooms throughout the United States, what stories are being told about Thomas Cole and Albert Bierstadt? How do these stories — often portrayed as benign fact — perpetuate harmful myths about American exceptionalism and who has the right to thrive on American soil? Nowadays, critical students of art history understand that paintings by Hudson River School artists helped solidify arguments in favor of American expansion and imperialism, which Trương references in the Translatio Imperii series. In this series, Trương harnesses the style of 19th century American landscape painting to represent sites bombed by the United States after World War II. She covers these paintings with black paint, save for a window in the shape of a brushstroke — a nod to the 1960s Brushstrokes series by American artist Roy Lichtenstein. We are meant to view these landscapes through the lens of modernism, a reminder that Abstract Expressionism was weaponized by the CIA during the Cold War to symbolize American individualism and freedom. On each frame, Trương affixes a bronze plate with the location depicted and year of bombing. Laos, the most bombed country in the world, is represented from an event in 2013. These intimately sized paintings are powerful in their directness: in picture after picture, it is clear that the United States has inflicted immeasurable global harm. This series provides an answer to the question: where are the paintings that confront this history of American imperialism?

Mythologies are built through allegories, symbols, and metaphors. The language of textiles often provides colloquial metaphors to describe the United States; think, “the fabric of American society,” or the use of “tapestry” to signify cultural diversity. Trương uses fabric in her practice to confront and challenge this metaphorical association. In the two series Mutiny in the Garden and From the Earth Rise Radiant Beings, diaphanous strips of hand-painted silk cascade down the paintings’ surfaces. The artist transfers imagery from historic textiles, ranging from an 18th-century George Washington design to various representations of chinoiserie, onto large panels of fabric, which she then cuts into smaller strips that render the pattern less legible. Historically, these source textiles circulated throughout the Western world, literally laying the mythologies of empire upon white bodies in the form of clothing, furniture, and household items. In disassociating these designs from their original, purportedly benign uses, Trương exposes their often nefarious meanings and implications.

In the history of the Asian diaspora, specifically of women, textiles have played a significant part in their racialization and forms of representation, a fact that Trương is specifically referencing in the aforementioned series. Textiles have historically marked difference for Asian Americans. In the 1875 “Case of Twenty-Two Lewd Chinese Women” (Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U.S. 275), a group of women arriving in San Francisco from China was not allowed to disembark the ship, because their attire was interpreted as unsatisfactory, immoral, and debauched. These women were sexualized vis-à-vis their dress — bright silk garments and ornamented hair — rather than nude bodies. In acknowledging this troubling history, Trương is also looking to transcend and reclaim it. For both the artist and this writer (Thai American), traditional Southeast Asian textiles hold special places in memories of our upbringings. Deeply saturated silk patterns and glittering gold threads remind us of our grandmothers, mothers, and special occasions during which such textiles were worn and displayed. While such fabrics were used against our Asian American women ancestors, Trương’s paintings provide a space for the diasporic descendants of these women to luxuriate in the intergenerational beauty of this important textile history.

In The Peril of Angel’s Breath (2018), a haunting portrait of Fred Korematsu, the late Japanese American civil rights activist, who refused to be interned during WWII, floats above the surface of the work. Around his visage we see a constellation of imagery: barracks of the internment camp Manzanar, plumes of a bomb explosion, Southeast Asian midcentury textile designs, and water rendered in a style that recalls Edo period Japanese painting. Rather than reading this work purely in mournful, tragic terms, Trương’s deft intermingling of multiple histories on a single plane points to a future in which such narratives can be openly discussed, acknowledged, and built upon. Trương’s paintings are sites where Asian American and Asian diasporic history are centralized and rendered anew in complex visual vocabularies that articulate melancholy, compassion, and hope for an unbounded future.

Liên Trương

Trương was born in Vietnam and emigrated to California when she was just eighteen months old. She earned a BFA from Humboldt State University in Arcata, CA, in 1999, and an MFA from Mills College, Oakland, CA, in 2001. Her work has been included in exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC; the National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Moscow, Russia; Nha San Collective, Hanoi, Vietnam; and Art Hong Kong; among others. She is the recipient of several awards and honors, including the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Grant, Whitton Fellowship from the Institute from the

Arts and Humanities, and the NC Arts Council Fellowship. Residencies include the Oakland Museum of California and the Marble House Project, Vermont. Trương’s work is in several public collections, including the Linda Lee Alter Collection of Art by Women at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia; DC Collection, Disaphol Chansiri, Chiang Mai, Thailand; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC; Cameron Art Museum, Wilmington, NC; and the Post Vidai Collection and Royal